Our Mysterious School Budget

Growing up in the ’burbs, my school district served three towns, but most students were less than a mile from any particular school, so we could walk. I remember the often-vocal disputes over the school budget, with my parents and their friends battling the senior voting block that would work to send the budget down in flames. Now, as I am about to graduate into senior citizenship myself, I can well relate to the tax burden people on fixed incomes feel. Still, I am happy to pay the price of living in a community with growing families. Washington would not be the same without a thriving community of young kids. Education represents one of the most significant line-items in the town budget—45 percent of the budget, in fact. I hoped to figure out how it is determined, so I set out to research why the education budget is what it is, and why it seems to fluctuate so much.

After reading some reporting in the Berkshire Eagle and then meeting with Kent Lew, the complexities of Massachusetts’ approach to financing education began to come into focus.

We are part of the Central Berkshire Regional School District (CBRSD), made up of seven towns: Becket, Cummington, Dalton, Hinsdale, Peru, Washington and Windsor. We combine forces to provide education for all of our students.The School District funds its budget with some state aid (called Chapter 70 funds), and the rest has to come from the towns. How it all gets divvied up is quite complicated.

Each year, the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) follows a complex formula to determine a “foundation” budget for every community. This represents a basic level of education for every student in Massachusetts. DESE then determines how much of that is to be funded by state aid and how much each town is required to contribute.

When the state determines how much each town has to pay, it considers the property values in the town, the potential growth in the tax base and the residents’ financial prosperity to come up with how much it thinks a given community can afford and should be spending on education.

Given those factors, a town’s required minimum can be volatile: There can be dramatic changes in income level in town, or property values might change, or we might show growth in our ability to raise revenue.

But the actual cost of providing an education for our students in Central Berkshires is higher than the State’s foundational budget. So the District has to assess an additional amount to make up that difference, which is called the Budget Balance. This balance is apportioned among the towns based on a five-year rolling average of the number of students each town has in the district—for Washington, that’s 53 students.

Transportation costs round out the district’s operating budget and aren’t part of the State’s foundational budget. These costs are assessed based on the same rolling five-year average of students.

So each year our budgeted CBRSD Operating Costs are made up of these three components: our state-determined Required Contribution, our portion of the Basic Budget Balance, and our portion of the Transportation budget.

For next year, in Washington these costs will average to around $14,328 per student. Because the state’s required contribution is based on local property values and incomes, that average cost per student varies widely across the seven towns. Becket, for instance, averages to roughly $20,000 per student, while Peru pays more like $11,000.

There is also a capital budget (the debt on school buildings), which is determined on a project basis. The annual debt payment on each project is apportioned based on the town’s number of students in that specific school, not district-wide. So, as Kent points out, “Becket-Washington School debt is covered basically by Becket and Washington. Dalton and Hinsdale have a few students attending, so they contribute a little.”

The fluctuation of student population across the district can impact operating assessments. Washington’s school-age population has been fairly constant, but many other towns have gone down in recent years. So our costs have gone up, even though we don’t have more students because we ended up with a higher proportion.

You might think this sounds an awful lot like an unfunded mandate from the state, but the state barred unfunded mandates years ago; so it is just a mysterious and convoluted formula. What is, in fact, an unfunded mandate is the transportation requirement for our vocational education students. When the state barred unfunded mandates, Voc. Ed. transportation was already in place, so it was not subject to that law.

Since our school district does not have any of its own vocational education programs, students attend Voc. Ed. outside the district, and it is our town’s responsibility to transport them there. They might attend Taconic High School in Pittsfield, about 30 minutes away; McCann Technical School in North Adams, about 45 minutes away, or Smith Vocational and Agricultural High School in Northampton, about 60 minutes away.

Where kids go is based on a number of factors, including which schools have programs they want to attend. Kent reports that Washington currently has six Voc. Ed. students attending three different schools, spread across the region.

The tuition for Voc. Ed. averages just under $20,000. But we get state aid from “Chapter 70 funds” of $5,100 per student. What is more challenging are the logistics and costs of transportation. We are required by state law to provide that transportation, and currently have to budget roughly $10,000 per student.

The Town is entitled to full reimbursement by the state for these transportation costs — “subject to appropriation” by the Ways and Means Committee at the Statehouse. Unfortunately, for at least the past seven years, the State appropriation for this has only been enough to cover about six percent of the cost, with taxpayers picking up the rest. This year, the reimbursement will be about 17 percent.

Further complicating the town’s budgeting process is the timing of students’ acceptance into Voc. Ed programs. “We don't find out definitively which new students got accepted and to which schools until July or August, after our budget has already been passed in May,” Kent says, “which makes it all a moving target, especially transportation.”

If this all sounds a little untenable, that’s because it is. Rural school districts are facing a financial crisis, as we simply don’t have the economies of scale of an urban or suburban district. We’ll all likely be hearing more about Statehouse debates over rural schools in the coming year.

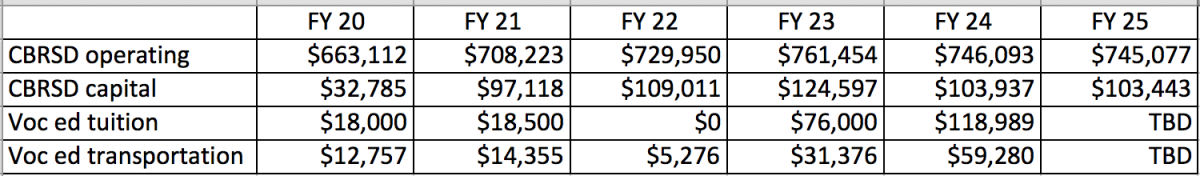

Washington's Education Costs